MR is the most common form of valvular heart disease (VHD) in the developed world, affecting 2% of people worldwide.3,10,15

For too long, mitral regurgitation (MR) has been undertreated, compromising patient outcomes. It's time to deliver targeted and effective treatments for moderate-to-severe and severe MR that improve cardiac function and change lives.1–4

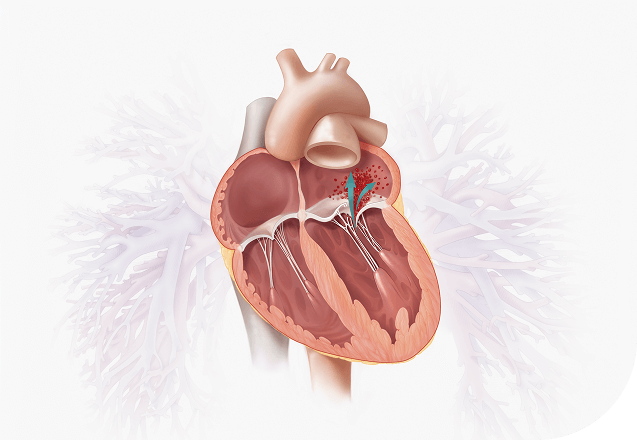

MR is backward blood flow during left ventricular systole, which can lead to progressive symptoms if left untreated. Structural changes to the heart can lead to atrial fibrillation, heart failure (HF) and pulmonary hypertension.5,6

MR is characterised by two distinct aetiologies:

The most common cause of DMR is mitral valve prolapse, which is defined by a spectrum of lesions.11

Any MR resulting from abnormalities/disease of the left ventricle (ventricular SMR) or left atrium (atrial SMR). There are no structural problems with the valve apparatus itself.9,10,13 Significant SMR has been shown to develop in around half of patients with myocardial infarction and up to 50% of patients with HF.14

MR is the most common form of valvular heart disease (VHD) in the developed world, affecting 2% of people worldwide.3,10,15

MR is the second most common VHD in Europe, affecting >19 million adults >65 years old, as extrapolated from a community study in Oxfordshire, UK.12,15,17,18

Up to 49% of patients with symptomatic MR go untreated.15

Effective treatment of SMR starts with optimisation of medical treatment.13 For patients with severe ventricular SMR and impaired left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), without concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD), who remain symptomatic despite guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) and cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT), if indicated, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) is the recommended treatment option, provided certain clinical and echocardiographic criteria* are fulfilled. Surgery may be considered in those unsuitable for TEER provided they do not have advanced heart failure.13

Symptomatic patients with severe atrial SMR under optimal medical therapy should be considered for mitral valve surgery, surgical ablation (if indicated) and left atrial appendage occlusion. TEER may be considered in those unsuitable for surgery after optimisation of medical therapy including rhythm control, when appropriate.13

*Please refer to criteria detailed in Table 7 of the European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS) Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease.13

Mitral TEER, also referred to as transcatheter mitral valve repair, is a percutaneous catheter-based approach that aims to restore mitral valve leaflet coaptation, thus reducing MR.19

Refer patients with severe, symptomatic MR despite GDMT to a Heart Team.13

Early recognition is key.20 Patients who progress to severe disease should be referred for evaluation to a Heart Team when intervention is considered.13 The ESC/EACTS guidelines specify that symptomatic patients with severe PMR who are anatomically suitable and at high surgical risk should be considered for TEER by the Heart Team.13 Additionally, TEER is recommended in patients with severe ventricular SMR and impaired LVEF, without CAD, who remain symptomatic despite GDMT and CRT (if indicated) and fulfil certain clinical and echocardiographic criteria.* TEER may be considered in patients with severe atrial SMR who are not eligible for surgery, provided symptoms persist after optimisation of medical therapy including rhythm control, when appropriate.13 The multidisciplinary team will carefully select the right treatment option for the patient, to ensure the best possible outcome.13,20

*Please refer to criteria detailed in Table 7 of the ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease.13

The following patients should be considered for TEER:

TEER is recommended for the following patients:

The following patients may be considered for TEER:

The following patients may be considered for TEER:

aPlease refer to criteria detailed in Table 7 of the ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease.

bPatients may be considered after careful evaluation of LVAD or heart transplantation. Percutaneous coronary intervention followed by TEER after re-evaluation of MR may be considered in symptomatic patients with chronic severe ventricular SMR and non-complex CAD.

The 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines mark a major shift in clinical practice for patients with ventricular SMR. With a Class I recommendation for intervention and a strong emphasis on early implementation of GDMT, they clearly set a new standard of care. Following these guidelines ensures MR patients receive evidence-based, timely, and optimal treatment across Europe and beyond.*

-Professor Mark Petrie

University of Glasgow, UK

*Expert opinions, advice and all other information expressed represent contributors' views and not necessarily those of Edwards Lifesciences.

The latest guidelines introduce pivotal changes in the management of MR.

For a listing of indications, contraindications, precautions, warnings, and potential adverse events, please refer to the Instructions for Use (consult eifu.edwards.com where applicable).

PP--EU-10019 v3.0